Introduction to Python

Contents

Introduction to Python¶

In this section we introduce Python programming and present examples illustrating key language features. We can learn the syntax of Python in a few days, but learning to use a language is more than just learning the syntax. Building a pool of experience that lets us be an efficient programmer is usually tough – as it requires working on good quality exercises for months, but it is doable and certainly very useful.

We assume no prior knowledge of Python, but experience with programming concepts or another programming language will help, but is not required to understand the material. Alhough each programming language is different (though not as different as their designers would like us to believe), they can be related along some dimensions.

Low-level versus high-level refers to whether we program using instructions and data objects at the level of the machine (something like move 64 bits of data from this location to another location) or whether we program using more abstract high level operations (like pop a menu on the screen) that have been provided by the language designer.

General versus targeted to an application domain refers to whether the primitive operations of the programming language are widely applicable or are fine-tuned to a specific domain or machine. For example,

SQLis designed for extracting information from relational databases, but you would’nt want to use it to build an operating system. SQL would be useless for that!!!Interpreted versus compiled refers to whether the sequence of instructions written by the programmer, called source code, is executed directly by a program called the

interpreterthat reads the code line by line and performs the specified action with code within the interpreter or whether it is first converted (by acompiler) into a sequence of machine-level primitive operations. There are adantages to both approaches. It is often easier to debug programs written in languages that are desgined to be interpreted, because then the interpreter can produce error messages that are easy to relate to the source code.

Python is a general purpose, interpreted, high-level programming language that we can use effectively to build almost any kind of program that does not need direct access to the computer’s hardware.

Note

In this website, we use Python, however, this book is not meant to be about Python. It will certainly help us learn Python, and that’s a good thing. But what we would like to focus on is how to write programs that solve problems. Once we figure that out then we can transfer our skill to any programming language.

Programming can dramatically improve our ability to collect and analyze information about the world, which in turn can lead to discoveries. In data science, the purpose of writing a program is to instruct a computer to carry out the steps of an analysis. Computers cannot study the world on their own, people must describe precisely what steps the computer should take in order to collect and analyze data, and those steps are expressed through programs.

Basic Python Data Types¶

One of the most basic feature of Python is that it is a Object-oriented programming language, which means everything inside Python is an object. When we write programs, we essentially specify a set of actions to perform that manipuates the object in some capacity. Sometimes we even call the object as value, and each value is a piece of data that a computer program works with such as a number or text. There are different types of values: 42 is an integer and “Hello!” is a string.

A variable is a just name that refers to a value, it gives us a way to associate names with objects. In mathematics and statistics, we usually use variable names like \(x\) and \(y\). In Python, we can use any word as a variable name as long as it starts with a letter or an underscore. However, it should not be a reserved word in Python such as for, while, class, lambda, etc. as these words encode special functionality in Python that we don’t want to overwrite!

Note

Although we mentioned that a variable is just a name, its not that simple. Programming languages let us describe computations so that computers can execute them, but this does not mean only computers have to read programs. It’s often best to write programs that are easy to read and an apt choice of variable names plays an important role in enhancing readability. You can read more about them here.

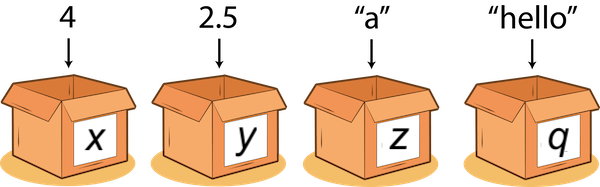

It can be helpful to think of a variable as a box that holds some information (a single number, a vector, a string, etc). We use the assignment operator = to assign a value to a variable. An assignment statement associates the name to the left of the = symbol with the object denoted by the expression to the right of the = symbol.

Fig. 2 Python Variables.¶

Image taken from: medium.com

Common built-in Python data types

See the Python 3 documentation for a summary of the standard built-in Python datatypes (dtype for short). In later chapters we will look into all of them as we use them to build simple programs.

\(\qquad\)

English name |

Type name |

Type Category |

Description |

Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

integer |

|

Numeric Type |

positive/negative whole numbers |

|

floating point number |

|

Numeric Type |

real number in decimal form |

|

boolean |

|

Boolean Values |

true or false |

|

string |

|

Sequence Type |

text |

|

list |

|

Sequence Type |

a collection of objects - mutable & ordered |

|

tuple |

|

Sequence Type |

a collection of objects - immutable & ordered |

|

dictionary |

|

Mapping Type |

mapping of key-value pairs |

|

none |

|

Null Object |

represents no value |

|

\(\qquad\) This table shows some of the built-in data types in Python along with examples of using them.

Numeric data types¶

There are three distinct numeric types: integers, floating point numbers, and complex numbers (not covered here). We can determine the type of an object by using Python’s in-built function type(). We can print the value of the object using another in-built function print(). You can find Pythons inbuilt functions here. A function is simply a set of code lines which can take some input, do processing on it and return some output. We will learn more about functions later on, but for now…

Let’s create a variable named x that stores the integer 7, which is the variable’s value:

x = 7

type(x)

int

The snippet \(x\)=7 is a statement. Each statement specifies a task to perform. The preceding statement creates \(x\) and uses the assignment symbol (=) to give \(x\) a value. The entire statement is an assignment variable that we read as “x is assigned the value 7”. The following statement creates a variable \(y\) and assigns to it the value 42. We will even use the print() function to see what its value is:

y = 42

print(y)

42

In Jupyter/IPython (an interactive version of Python, through which this content was written), the last line of a cell will automatically return as an output and so we don’t actually need to explicitly state print().

y # Anything after the pound/hash symbol is a comment and will not be run

42

Python allows multiple assignment as well. The statement

x, y = 1, 2

binds x to 1 and y to 2. All of the expressions on the right-hand side of the assignment are evaluated before any bindings are changed. This is convenient since it allows us to use multiple assignment to swap the bindings of two variables.

For examples, the code

x, y = 1, 2

x, y = y, x

print('x =', x)

print('y =', y)

will print

x = 2

y = 1

pi = 3.14 # assigning a decimal point number results in a float type

type(pi)

float

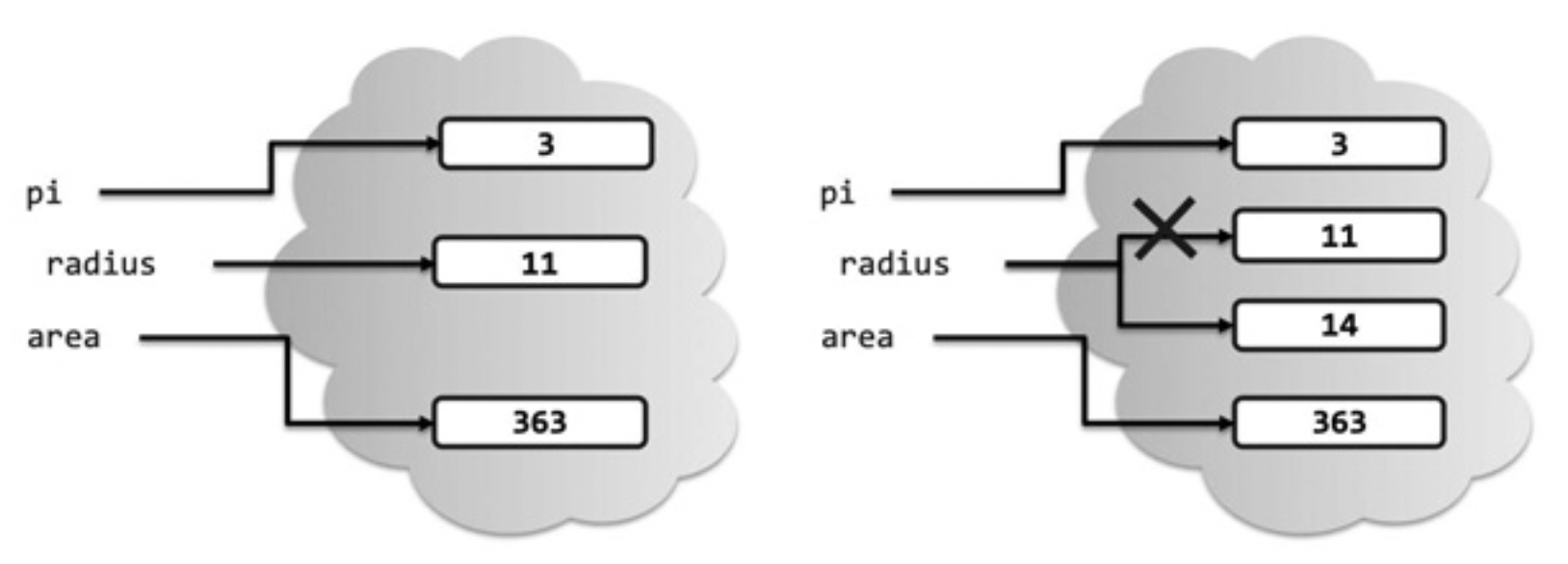

Consider the code

pi = 3

radius = 11

area = pi * (radius**2)

radius = 14

The code first binds the names pi and radius to different objects of type int. It then binds the name area to a third object of type int. This is depicted on the left side of figure below.

Fig. 3 Variable Assignment.¶

If the program then executes radius = 14, the name radius is rebound to a different object of type int as shown on the right side.

Note

This assignment has no effect on the value to which area is bound, it will still keep denoting the object by the expression 3*(11**2)

Arithmetic Operators¶

The code above showed example of arithmetic operator, below is a table of the syntax for common arithmetic operations in Python:

Operator |

Description |

|---|---|

|

addition |

|

subtraction |

|

multiplication |

|

division |

|

exponentiation |

|

integer division / floor division |

|

modulo |

Let’s have a go at applying these operators to numeric types and observe the results.

1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 # add

15

11 * 3.14159 # multiply

34.55749

2 ** 10 # exponent

1024

Caution

Division may produce a differnt dtype than expected, it will change int to float

num = 5

type(num)

int

num / num # divison

1.0

When we use the syntax //, it allows us to do “integer division” and retain the int data type. It gives us the quotient after division.

50 / 3

16.666666666666668

50 // 3

16

type(50 // 3)

int

We call this the integer division because its like calling the int function on the result of the division.

int(50 // 3)

16

Casting in Python

The % is called the "modulo" operator and this gives us the remainder after doing the division. In case you are wondering how its spelled, we call the below operation as 50 mod 3

50 % 3

2

We can also perform the modulo operation on objects of float type.

50.5 % 3

2.5

Strings¶

Much of data is not stored in the form of numbers, but as text, which is represented in a computer in the form of a string. We can think of string as a sequence of characters, that can represent a word, a sentence, or even the contents of every book in a library.

We write strings as characters enclosed with either:

single quotes, e.g.,

'Data'double quotes, e.g.,

"Science"

There is no difference between the two methods, but there are some cases where it’s useful to have them both.

We can even add two strings together and the result will also be a string, for instance, adding two strings together produces another string. This expression is still an addition expression, but it is combining a different type of value.

'Data' + "Science"

'DataScience'

The addition operator + is said to be overloaded as it carries different meaning depending on the type of object it works on. When its used on numeric type it means addition, but when used for strings it means concantenation. In the above example it combines these two strings without regard for their contents. It doesn’t add a space because these are different words; that’s up to the programmer (you) to specify. We can add space between words by using an empty string with space.

'Data' + ' ' + 'Science'

'Data Science'

"""

Everything enclosed inside triple quotes is considered to be a multi-line

comment and will not be executed

"""

'Python' + 3

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-2-2573cb83bf00> in <module>

3 comment and will not be executed

4 """

----> 5 'Python' + 3

TypeError: can only concatenate str (not "int") to str

Note

We cannot concatenate an integer to string, we will first need to cast the integer into a string by using str() or enclosing the integer inside quotes, for example,

'Python' + str(3)

or

'Python' + '3'

Double-quoted strings could be useful in certain situations like

"I can't use single-quoted strings here"

"I can't use single-quoted strings here"

quote = 'Tony Stark: "I am Iron Man."'

print(quote)

type(quote)

Tony Stark: "I am Iron Man."

str

None¶

There are special object in Python that has no value, we call this type as NoneType. This type has only one possible value - None

x = None

print(x)

None

type(x)

NoneType

Branching Programs¶

The kinds of computations we have been looking at so far are called straight-line programs. This means they execute code one statement at a time, one after another, in the order in which they appear and stop when they run out of statements to execute. We can’t really describe anything interesting with straight-line programs, as they can be downright boring.

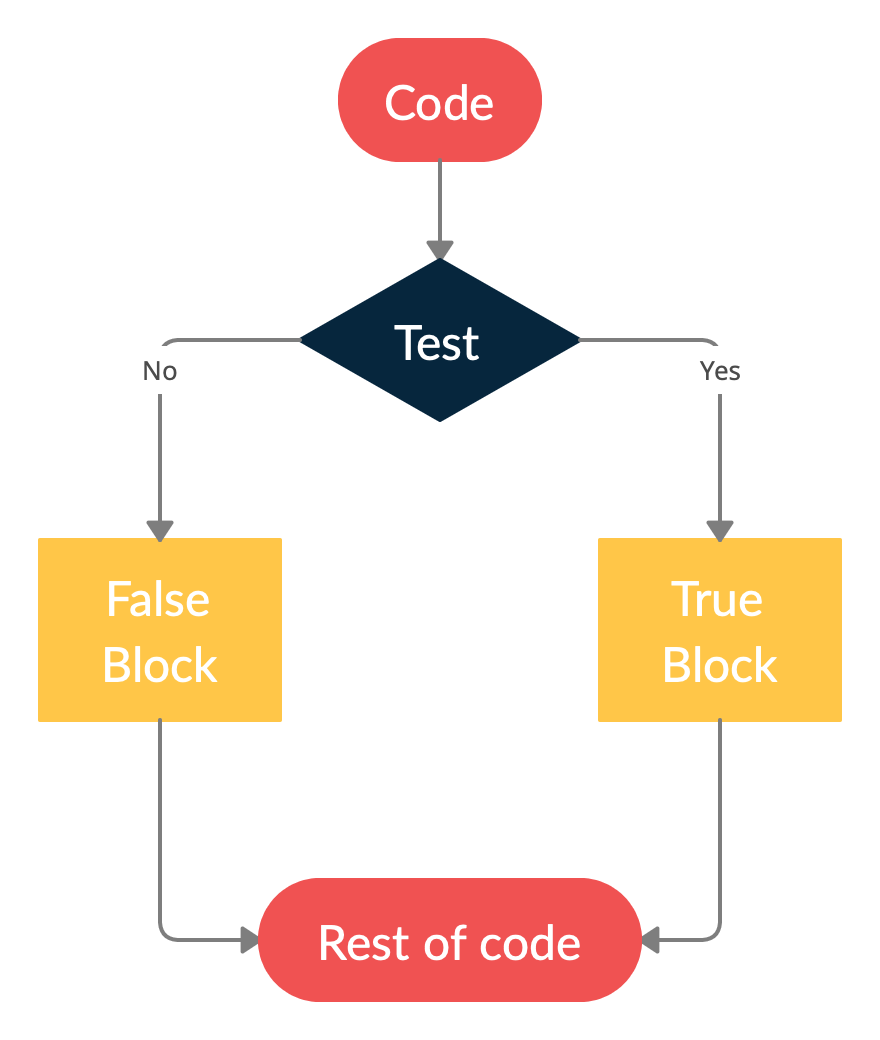

Branching programs are more interesting, the simplest branchihng programs is a conditional. It has three parts:

A

testis performed to check if a statement is evaluated as either True or Falseifthe test evaluates as True then a block of code is executedelse, an optional block of code gets executed if the test is False

After a conditional statement is executed, execution resumes at the code followiing the statement

Fig. 4 Branching Program Flowchart.¶

Boolean¶

In Python, we perform test using an objedct called the Boolean, which has the type bool and has only two values: True or False

Truth = True

Truth

True

type(Truth)

bool

lies = False

type(lies)

bool

In Python, branching program can take the following form

if Boolean expression:

block of code

else:

block of code

or

if Boolean expression:

block of code

Comparison Operators¶

Boolean expressions are created in Python with the help of comparison operators. Python includes a variety of operators that compare values. For example, we can check if 3 is larger than 1 + 1 using the comparison operator '>' and it will return a boolean value. There are other comparison operators in Python

Operator |

Description |

|---|---|

|

is |

|

is |

|

is |

|

is |

|

is |

|

is |

|

is |

"Machine learning" == "Solve all the world's problems"

False

An expression can contain multiple comparison and they all must hold in order for the whole expression to be True. For example, we can express that 1+1 is between 1 and 3 using the following expression.

1 < 1 + 1 < 3

True

Strings can also be compared, and their order is alphabetical. A shorter string is less than a longer string that begins with the shorter string.

"Dog" > "Catastrophe" > "Cat"

True

Let’s use comparison operators to create the following program that prints "Even" if the value of the variable \(x\) is even and "Odd" otherwise:

if x%2 == 0:

print('Even')

else:

print('Odd')

print('Done with conditional')

The expression x%2 == 0 will evaluate to True when the remainder of \(x\) divided by 2 is 0, and False otherwise. Remember than == is used for comparison, since = is reserved for assignment.

The main points to notice:

Use keywords

if,elifandelseThe colon

:ends each conditional expressionIndentation (by 4 empty space) defines code blocks

In an

ifstatement, the first block whose conditional statement returnsTrueis executed and the program exits theifblockifstatements don’t necessarily needeliforelseeliflets us check several conditionselselets us evaluate a default block if all other conditions areFalsethe end of the entire

ifstatement is where the indentation returns to the same level as the firstifkeyword

Indentation is semantically meaningful in Python. For example, if the last statement in the above code were indented, it would be part of the block of code associated with the else, rather than the block of code following the conditional assignment.

Python is unusual in using indentation this way. Most other programmig languages use bracketing symbols to delineate blocks of code, see comparison below,

if 20 > 18:

print("20 is greater than 18")

if (20 > 18) {

cout << "20 is greater than 18";

}

An advantage of Python approach is that it ensures that the visual structure of a program is an accurate representation of its semantic structure.

Nested Conditionals¶

Sometimes our conditional statement may have another conditional, and they are called nested conditional. The code below contains nested conditionals in both branches of the top-level if statement.

x = 20

if x%2 == 0:

if x%3 == 0:

print('Divisible by 2 and 3')

else:

print('Divisible by 2 and not by 3')

elif x%3 == 0:

print('Divisible by 3 and not by 2')

Divisible by 2 and not by 3

It is often convenient to use a compound Boolean expression in the test of a conditional. In order to create compound Boolean expression we use so called “Boolean operators” and, or, not. Their use case are shown below, and they evaluate to either True or False.

Operator |

Description |

|---|---|

|

are |

|

is at least one of |

|

is |

True and True

True

True or False and True

True

Let’s look at an example of how they can be used to compare three numbers…

x, y, z = 13, 34, 23

if x < y and x < z:

print('x is least')

elif y < z:

print('y is least')

else:

print('z is least')

x is least

Try yourself

Write a program that examines three variables - \(x\), \(y\), and \(z\) - and prints the largest even number among them. If none of them are even, it should print the smallest value of the three.

Python also supports conditional expressions as well as conditional statements. They take the form

express1 if condition else express2

If the condition evaluates to True, the value of the entire expression is express1; otherwise it is express2. For example, the statement

x = y if y > z else z

sets \(x\) to the maximum of \(y\) and \(z\).

Visualizing Branching Programs¶

In the preceding section we saw how conditional statements (if..elif...else statements) help us control the flow of our code. We can have as many conditional statements as we like, but only the condition that evaluates as True will get executed. We can see how the computer performs the execution of code in the visulization below. You can click on next to see the changes that take place inside the machine’s memory while executing the code.

Note

We haven’t spoken about frames in Python, but we will encounter them when we talk about functions, we will use this visualization in future as we encounter more sophisticated programming concepts and objects in later chapters.

We can see that even though there are 12 lines of code the computer performs the execution of code in 8 steps. In the first step it assigns the values to the variables we specified, and then changes the value of \(x\) based on the condition we specified in the second line of code. We can see how the computer jumps straight to the else code block when it encounters that the if condition is found to be false. It then prints the output and comes out of the entire if...else code block and moves on to line 12.

Another point to note is that when the code at print(float(x)) is executed, it changes the value of \(x\) to a floating point number and prints its output, but there is no change in the actual value of variable \(x\) in computer’s memory. The only time the actual value of the variable changes is when we specify them explicity (which we do in code line 13).

Conditionals allow us to write programs that are more interesting than straight-line programs, but this class of branching programs is still quite limited. There is very little we can do with conditions and numeric data type, in order to construct more complex programs we will look at sequence type objects. They open up the option to construct another important programming language concept, iteration.